As the salmon industry in BC increased rapidly, so did the need for labour and higher production rates in the canneries. Canned salmon was in demand, and canneries were desperate to hire cheap labour to process the massive amounts of fish their fisherman were able to bring in. In the 1870’s “China Bosses” began organizing teams of Chinese workers to fill labour shortages under contracts with the canneries, but the introduction of the head tax added stress to an already maxed labour market. Skilled workers, such as the Chinese or Aboriginal “Butcher Gangs,” were able to charge more for their skills as jobs were plentiful, but workers were scarce. Canneries turned to mechanization for relief, and in the early 1900’s machines began to enter the cannery line.

Canadian-born E. A. Smith took up the charge to invent a machine to help cut down on labour costs, speed up production, and replace the expensive skilled Chinese butcher teams. E. A. Smith was born in London, Ontario, and moved to Washington in 1898 for work. Smith eventually invested heavily in the Alaskan Fishermens’ Union, and was disappointed in the losses he suffered due to labour shortages. Smith laboured for years to invent his butchering machine, going further and further into debt until his first model debuted in Washington canneries in 1903. The machine was officially called “The Smith Butchering Machine,” or “The Iron Butcher,” but soon came to be known as the “Iron Chink” as it displaced so many Chinese butcher teams. Smith continued to repair and improve earlier models, until a patent was passed in 1905. The butcher machines were advertised in newspapers as: “The Big Opportunity ARE YOU PREPARED? Chinese Labor will be Scarce – Contract Prices will be Raised – The “Iron Chink” is Your Only Relief.” Clearly, this exceptional machine made an impact on the canning industry in a short period of time.

His butchering machine was unique due to its speed and compact size: the circular innards allowed for the butcher tasks to be compressed into a much more efficient and effective cycle. A table was attached to the side where one worker would cut off the head and tail of the fish with a bandsaw blade. Next, a second worker would feed the fish into the machine, where the fins and gills were removed, as well as some scales, and, in later models, the fish would be gutted and cleaned before being sent down the line. The butchers were incredibly fast, allowing for forty chinook salmon to be butchered per minute, or up to seventy pink or sockeye salmon. Eventually, a third worker was added to remove the roe from the fish. So, this one machine replaced a thirty-man butcher team with two or three workers: the savings in wages gave the canneries the opportunity to quickly pay off their investment in mechanization.

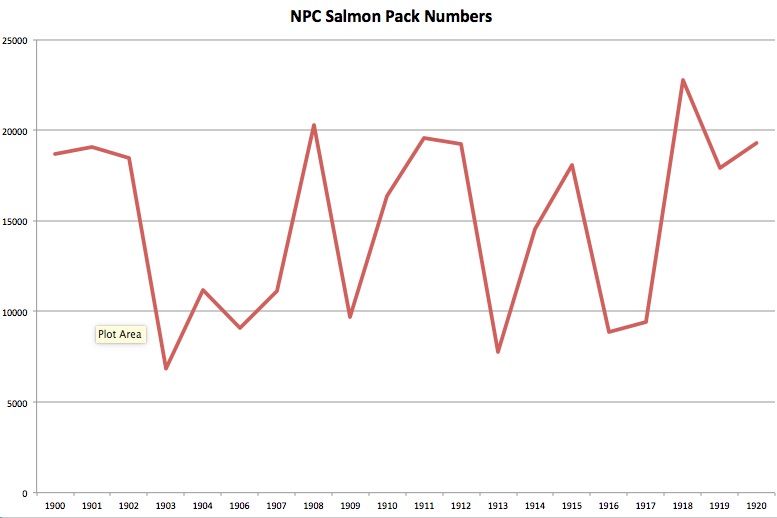

The Iron Butcher was introduced to the North Pacific Cannery in June of 1915.[1] The figures included below detail the Salmon Pack numbers, or production rates, of the North Pacific Cannery from 1900 to 1920 (Figure 1), and the comparison of money paid to independent Chinese workers and those working under contracts (Figure 2). In looking at these graphs, we can see that if the Iron Butcher was indeed installed in 1915, it did not provide a massive increase in salmon packs in the first few years. However, this could be due partly to low numbers of salmon present, and possibly an older model of the Iron Butcher that did not clean the fish, only butcher it. There is a massive spike in production in 1918, which could be a result of the installation of the Iron Butcher, and potentially higher salmon populations.

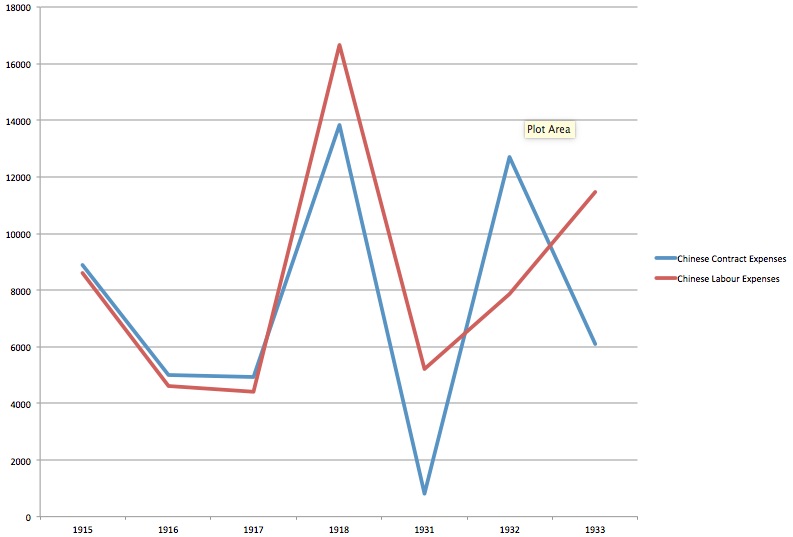

Figure 2 attempts to show if the Iron Butcher managed to displace Chinese workers or not. In looking at both lines, it is not until the 1930’s that there is a large difference in pay to contract and independent workers. However, the amount paid to Chinese workers overall directly after 1915 declines steeply: this could be due to layoffs associated with the Iron Butcher, with the Chinese workers returning to different types of cannery work in the years following. Throughout there is a trend of the independent Chinese workers being paid more than the contract workers: this could be due to the skill level of workers being hired, or the canneries taking advantage of the Chinese.

In conclusion, E. A. Smith’s Iron Butcher machine revolutionized the canning process: not only did it allow for more fish to be processed, it allowed canneries to save money through less wasted fish, and less workers’ salaries. The Iron Butcher was designed to be compact, timely, and to replace Chinese butcher teams: it was essential in dictating the pace of the assembly line. According to data from the Port Edward Archives, the Iron Butcher does not appear to have an immediate effect on the pack numbers or amounts being paid to Chinese workers. However, the years following the installation of the Butcher do see rapid fluctuations in pack totals and in the amounts paid to contract and independent Chinese workers. While we cannot say for sure if the Iron Butcher displaced many Chinese workers in particular, it can be said that it greatly changed the canning line.

Figure 1: Salmon Pack numbers from 1900-1920. Found in “Canneries, Etc.” in file folder “Blyth, Gladys” in Port Edward Archive’s Filing Cabinet.

Figure 2: Comparison of the amounts paid to Chinese Independent (red) and Chinese Contract (blue) workers. Data obtained from MS 2 Vol 45 and 47, Port Edward Archives.

[1] This is proven by the purchase of 76 “Bolt’s for Iron Chink” in the 1915 ledger, as well as the lack of reference to an Iron Butcher being present in the 1915 fire insurance plan. The bolts are not listed in the Iron Butcher’s parts manuals in the Port Edward and Gulf of Georgia Archives, and can therefore be assumed to be parts for installation. Purchases of parts for the butcher only appear in 1915, 1917 and 1923, showing how reliable the butchers were. Though there are a few references to multiple canning lines at the North Pacific Cannery, all maps up to the 1960’s in the archives detail a “One-Line Cannery Plan,” and have space marked out for one Iron Butcher. As well, in the archives there is a detailed list of the machinery in the cannery when it was declared a historic site, with no Iron Butcher listed. Therefore, we can assume that the Iron Butcher currently in the cannery is from Sunnyside Cannery, which boasted three Iron Butchers, or one of the other canneries that were disassembled in the area.