The Prince Rupert City website lists The Empire, founded by editor John Houston in July 1907, as the first newspaper established Prince Rupert. Tucked away at the Prince Rupert City and Regional Archives and hidden deep in its fragile pages are sentiments that may change how the newspaper is remembered. A reading of the newspaper’s inaugural six months of publication revealed a distain towards the presence of Asian labour at the local canneries coupled with concerns for the future of Prince Rupert’s white settlement. This analysis was influenced by a similar argument put forth by sociologist Renisa Mawani in Colonial Proximities Crossracial Encounters and Juridical Truths in British Columbia, 1871-1921. Mawani asserted that the dependence on Asian workers in the Vancouver canneries was twofold: the cannery owners relied on their cheap, racialized labour, and the local economy was contingent upon the wealth produced by canneries. However, the employment of Asian labourers was met with opposition from the nearby white residents. They were concerned that the racial mixing engendered by canneries would imperil the future of their white settlement. Given The Empire’s attitude of Asian cannery workers, Mawani’s argument can be extrapolated to include the canneries of the North Coast. Although The Empire only sheds lights on Houston’s perspective, the newspaper remains a significant source due to its status as the first newspaper of Prince Rupert and, more importantly, its ability to disseminate his views while reporting on those of the populace.

Published in October, Houston’s headline article “Should Take a Stand and Stick to It” summarized his views on Asian labour. He lamented the presence of “a few Japanese employed in salmon canneries and a few Chinese employed as cooks and as domestic servants” for their effect on the establishment of Prince Rupert as a “white man’s town”. Without the competition of “Japanese and Chinese coolies”, Houston was sure that “the best class of people” – which he defined as “white men and their families” – would populate Prince Rupert and Norther British Columbia “if they know it is a white man’s country”. He used “the mistakes made in Victoria and Vancouver” as cautionary tales to support a boycott on Asian immigration.

Although Houston was concerned with the employment of Japanese and Chinese labourers, he feared them for different reasons. According to Houston’s November article “There Are No Canadian Fishermen”, the Japanese fishermen fulfilled positions meant for white men: “there is NOT ONE CANADIAN employed as a fisherman on the north coast of British Columbia; that that employment has passed into the hands of Japanese Coolies, through the GREED of cannery owners classed as Canadians”. This differed from his concern for Chinese labourers, premised on their supposed ability to contaminate the white population. In his November article “White People Have No Choice”, he lamented that “The people who live at Prince Rupert should not be compelled to get their clothes washed at a Chinese laundry or be forced to eat sour-dough bread made by Chinese cooks”.

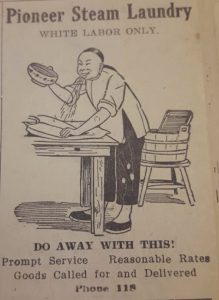

There is further evidence to suggest that the fear of Chinese contamination was shared among some of the first citizens of Prince Rupert. This communal anxiety can be traced alongside the establishment of Prince Rupert’s first white laundromat. Due to the absence of women in newly formed industry towns, Chinese labourers took on typically female domestic roles as mentioned by Houston in his article “Should Take a Stand and Stick to It”. Nearly two months after stating that “White People Have No Choice”, Houston reported that “Residents of Prince Rupert who are tired of doing business with the Chinese laundryman have arranged to patronize a white steam laundry at Vancouver”. The fact that white residents would rather send their soiled laundry down the coast rather than have it handled by a Chinese labourer speaks volumes about collective feelings of racial anxiety. This development can be paired with a 1912 advertisement for Pioneer Steam Laundry that depicts a caricature of a Chinese man spitting onto laundry with the caption “White Labor Only”. It can be surmised that in the five years between the article and the advertisement, a laundromat was opened to satisfy the needs of a white clientele.

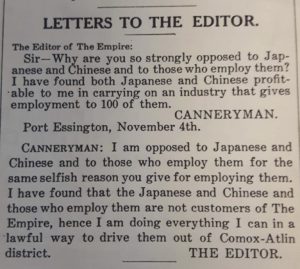

While other white residents may have experienced his fear of Chinese contamination, it is prudent to remember that not all of Houston’s opinions were universal among the early Prince Rupert populace. During the inaugural six months of publication, three people addressed letters to the editor regarding Asian labour. One letter asked why the editor “advocate(ed) the non-employment of Japanese”, to which Houston responded that “the employment of Japanese coolies… drives white men out of the province”. For Houston, this was a problem because “White men… are of more benefit to a community than men of any of the Asiatic races”. A second letter, attributed to “Canneryman”, questioned why the editor was “so strongly opposed to Japanese and Chinese and to those who employ them” in which Houston comically replied that they “are no customers of The Empire” hence he is justified in “driv(ing) them out of Comox-Atlin district.”. Only one of the letters aligned with rhetoric typical of The Empire. Authored by “White Pioneers” in anticipation of the general election, the letter calls for “Workingmen, although your stomachs through eating Asiatic-coolie-cooked food have become like those of a crocodile, do not let your brains become useless.”

The Empire was founded in the midst of the clearing of the town site, and its sentiments reveal that white residents were considered more desirable than Asian workers. A reading of its first six months of publication demonstrates that these passions were aroused by the employment of racialized labour at local canneries. Although The Empire’s attitude towards Asian labourers cannot be inferred onto the entire 1907 population of Prince Rupert, Houston’s beliefs cement his place in history as a white activist agitating for the exclusion of Asian labourers.

Photographs

Houston, John and ‘Canneryman’. “Letters to the Editor.” The Empire (Prince Rupert City and Regional Archives, BC), 9 November 1907: 2.

“Pioneer Laundry Advertisement.” Prince Rupert Journal (Prince Rupert City and Regional Archives, BC), 28 August 1912: 3.

Sources

City of Prince Rupert. “Community: About Prince Rupert.” 2015: http://www.princerupert.ca/community/about.

Houston, John. “Patronize a White Steam Laundry.” The Empire (Prince Rupert City and Regional Archives, BC), 4 January 1908: 1.

Houston, John. “Should Take a Stand and Stick to It.” The Empire (Prince Rupert City and Regional Archives, BC), 5 October 1907: 1.

Houston, John. “There Are No Canadian Fishermen.” The Empire (Prince Rupert City and Regional Archives, BC), 30 November 1907: 4.

Houston, John. “White People Have No Choice.” The Empire (Prince Rupert City and Regional Archives, BC), 9 November 1907: 4.

Houston, John and ‘Canneryman’. “Letters to the Editor.” The Empire (Prince Rupert City and Regional Archives, BC), 9 November 1907: 2.

Houston, John and ‘C. M. G.’. “Letters to the Editor.” The Empire (Prince Rupert City and Regional Archives, BC), 14 December 14 1907: 3.

Houston, John and ‘White Pioneers’. “Letters to the Editor.” The Empire (Prince Rupert City and Regional Archives, BC), 2 November 1907: 2.

Mawani, Renisa. Colonial Proximities Crossracial Encounters and Juridical Truths in British Columbia, 1871-1921. Vancouver: UBC Press, 2009: 38.

“Pioneer Laundry Advertisement.” Prince Rupert Journal (Prince Rupert City and Regional Archives, BC), 28 August 1912: 3.