In the late nineteenth century, many photographs were taken of indigenous people and their villages. George Dawson, a surveyor during this period used the photos to “make remote regions of BC legible in ways that both anticipated and facilitated their emergence as resource landscapes.”[1] Photographs were by land surveyors for the British Columbia government became much more influential, and they were used to market indigenous people and communities for the profit of white spectators in urban centres, both in Canada and the United States. Photographers used such photos to commercialize and idealize an image of vanishing indigenous culture.

The rise of photographs as tourist souvenirs began in the late nineteenth century. According to Carol Williams, “Museums sought photographs of early Indian life as they were valuable sources for displays and dioramas which reconstruct the pre-settlement existence of northwest cultural groups.”[2] A related sector was tourism, white North Americans wanted to see “Authentic Indians”. They subsequently bought into the idea that the indigenous were a dying race, and that these photos had encapsulated a vanishing people and grew out of a fascination with pre-colonial life. Historian Page Raibmon writes that “tourists saw vanishing Indians; missionaries and government agents saw shiftless wanderers.”[3] While the government pushed assimilation, tourists sought a pre-colonial experience. These competing objectives co-existed for a significant period of time.

Photography was an important way that this fascination with pre-contact culture was commodified and shared with wide audiences. Richard Maynard, originally a government photographer, and his wife Hannah became active participants in a growing tourism sector. They used photographs, taken by Maynard and others, largely taken on the north coast of Vancouver Island. Hannah in particular used portraits of indigenous people in non-European clothing as a common visual trop to foster this nostalgic ideal.[4] Another photographer who captured indigenous ways of life was Edward Curtis. Curtis’ objective was to capture what he saw as a dying race, and he attempted to enlighten white Americans about a culture that predated them, had immense value, and most importantly, was disappearing.[5]

Figure 1

The photos themselves depict indigenous people in what colonizers assumed to be traditional clothing. Figure 1, a photograph taken by the Maynards, show indigenous people in their traditional community, hunting for clams.[6] The photo depicts a picturesque landscape with indigenous people wearing pre-contact clothes, while using baskets. Baskets were an extremely popular souvenir for Euro-North Americans visiting coastal villages.[7] Figure 2, also from the Maynard collection, depicts a young indigenous woman in western clothing.[8] Compared to the first photograph this one appears to mourn the traditions of the indigenous people. The young woman is wearing the clothes of the colonizer, but her hair is braided in a seemingly traditional, indigenous way.

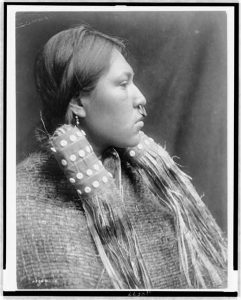

Figure 2

Edward Curtis’s photographs were greatly sought after. The broader fascination with pre-colonial indigenous culture made Curtis’s photos increasingly popular. Figure 3, entitled “Kotsuis and Hohhuq – Nakoaktok” renders two indigenous men in traditional masks.[9] The photo is staged, with a backdrop and a wooden floor below the two men. The masks they wear hide most of their bodies from view, all we see is the significance of the large bird beak. The photo may be staged, yet it shows the explicit authenticity white North Americans were searching for.

Figure 3

Figure 4 is a portrait of a young woman taken by Curtis entitled, “Hesquiat Maiden”.[10] This portrait, like figure 2 by the Maynards, both portray young indigenous women. Yet in this image, the woman dons traditional clothes and piercings. There is no indication of western influence, and she is presented to Euro-North American consumers as a figure from the pre-contact age. She represents, to quote Raibmon, “‘historical’ as well as ‘natural’ attractions.”[11] Although Curtis often claimed that he wanted to show the truth about indigenous culture, before contact and during peace,[12] he nonetheless reinforced the image of “authentic Indian” and preserved that image in the face of a broader assumption about vanishing.

Figure 4

The photographs of indigenous people taken by Euro-North Americans in the late nineteenth century became infatuating for the general public. They reveal a fascination with pre-contact indigenous culture. One outcome of this interest was the commodification of idealized images of indigenous people. Even photographs taken without this intent came to part of outsiders’ desire see an “Authentic Indian” before he or she vanished.

Bibliography

Curtis, Edward. “Hesquiat Maiden.” 1915. Pacific Northwest and Alaska. https://edwardcurtis.com/edward-curtis/regions/pacific-northwest-alaska/

Curtis, Edward. “Kotsuis and Hohhuq – Nakoaktok.” 1914. Pacific Northwest and Alaska. https://edwardcurtis.com/edward-curtis/regions/pacific-northwest-alaska/

Egan, Shannon. ““Yet in a Primitive Condition”: Edward S. Curtis’s North American Indian.” American Art 20, no. 3 (2006): 58-83.

Grek-Martin, Jason. “Vanishing the Haida: George Dawson’s Ethnographic Vision and the Making of Settler Space on the Queen Charlotte Islands in the Late Nineteenth Century.” Canadian Geographer 51, no. 3 (2007): 373–98.

Maynard, Hannah. “Studio portrait (full-length) of an Indigenous sitter taken at a photographic studio attributed to Charles Gentile studio.” 1866-1867. Maynard Family Collection. BC Archives, Royal BC Museum.

Maynard, Hannah. “Clam Hunt.” 1866-1867. Maynard Family Collection. BC Archives, Royal BC Museum.

[1] Dawson quoted in Jason Grek-Martin, “Vanishing the Haida: George Dawson’s Ethnographic Vision and the Making of Settler on the Queen Charlotte Islands in the Late Nineteenth Century,” Canadian Geographer 51, no. 3 (2007): 378.

[2] Carol Williams, Framing the West: Race, Gender, and the Photographic Frontier in the Pacific Northwest (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003), 190.

[3] Paige Raibmon, Authentic Indians: Episodes of Encounter from the Late-Nineteenth-Century Northwest Coast (Durham: Duke University Press, 2005) 116.

[4] Williams, Framing the West: 188.

[5]Shannon Egan, ““Yet in a Primitive Condition”: Edward S. Curtis’s North American Indian,” American Art 20, no. 3 (2006): 58-83.

[6] Hannah Maynard, “Clam Hunt,” 1866-1867. Maynard Family Collection. BC Archives, Royal BC Museum.

[7] Raibmon, Authentic Indians, 147.

[8] Hannah Maynard, “Studio portrait (full-length) of an Indigenous sitter taken at a photographic studio attributed to Charles Gentile studio,” 1866-1867. Maynard Family Collection. BC Archives, Royal BC Museum.

[9] Edward Curtis, “Kotsuis and Hohhuq – Nakoaktok,” 191. Pacific Northwest and Alaska.

[10] Edward Curtis, “Hesquiat Maiden,” 1915. Pacific Northwest and Alaska.

[11] Raibmon, Authentic Indians, 141.

[12] Egan, “Yet in a Primitive Condition” 66.