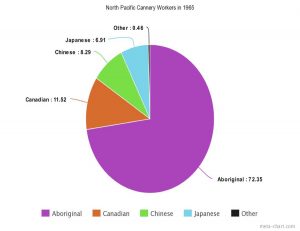

For my archival research I examined 217 individual records of employment from the North Pacific Cannery in 1965 and from these records much is revealed about the First Nations workforce and the unique relationship they had with the cannery as the majority workforce. First Nations employees accounted for over 72% of the workforce in 1965 and although there were First Nations workers were present at the cannery all year, most were only employed during the busy summer months of July and August. This duration is especially short compared to the Japanese employees and the white employees who worked an average of 4 months a year despite occupying far fewer positions in the cannery. This pattern of employment demonstrates the independence of the First Nations workforce and suggests that they took advantage of decent wage labour in the summer before returning home to pursue other interests or work. These short periods of employment for First Nations workers also embrace a long history where many aboriginal populations took advantage of cannery work during the summer and maintained a subsistence lifestyle throughout the rest of the year.[1] The North Pacific Cannery and First Nations employees clearly maintained a relationship of mutual benefits, as many workers returned to the remote cannery every summer despite only being employed for short durations of time. Evidence of loyal employment is also seen in the 1965 records of employment, which indicate that the average First Nations worker had been with the company for 4.5 years.

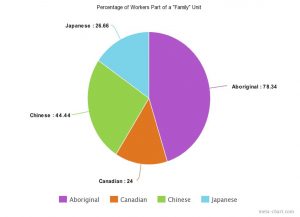

In addition to enjoying a mutually beneficial relationship between the cannery and First Nation employees, many Aboriginal workers could be incentivized to join the cannery with their family members. The employment records of 1965 reveal a unique pattern of First Nation family “units” being employed together during the season. Although some employment records indicate husband and wife pairs, most lack such detail and as a result I am defining a family unit as a group of two or more people who share the same last name and “ethnicity” in the records. The First Nations family units made up 78% of the aboriginal workforce, in comparison the Chinese family units only accounted for 44% of the total Chinese workforce. This contrast highlights the unique position of many First Nation workers at the North Pacific Cannery, as they were often working alongside their families which could range from 2 to 13 people. The First Nation family units rarely followed the expected pattern of husband and wife duos, in fact the smaller units were most commonly made up of all women or all men. The advantages of having family ties can be seen when examining the occupations of First Nation workers in 1965, as many family units were able to do the same job (divided by gender). An example of this can be seen in the records of the Aksidan family, which was comprised of three women who all worked as washers in the summer of 1965. Another example can be seen in the records of the Calder family, as the three men worked as casual labourers and the sole woman worked as a washer. Cannery work often required individuals to remain in a small area for long periods and as a result they often bonded closely with the immediate people surrounding them. Ultimately, the cannery actively hiring families would help to provide a cohesive labour force and encourage a positive and familiar atmosphere by placing family members in similar roles.

In addition to enjoying a mutually beneficial relationship between the cannery and First Nation employees, many Aboriginal workers could be incentivized to join the cannery with their family members. The employment records of 1965 reveal a unique pattern of First Nation family “units” being employed together during the season. Although some employment records indicate husband and wife pairs, most lack such detail and as a result I am defining a family unit as a group of two or more people who share the same last name and “ethnicity” in the records. The First Nations family units made up 78% of the aboriginal workforce, in comparison the Chinese family units only accounted for 44% of the total Chinese workforce. This contrast highlights the unique position of many First Nation workers at the North Pacific Cannery, as they were often working alongside their families which could range from 2 to 13 people. The First Nation family units rarely followed the expected pattern of husband and wife duos, in fact the smaller units were most commonly made up of all women or all men. The advantages of having family ties can be seen when examining the occupations of First Nation workers in 1965, as many family units were able to do the same job (divided by gender). An example of this can be seen in the records of the Aksidan family, which was comprised of three women who all worked as washers in the summer of 1965. Another example can be seen in the records of the Calder family, as the three men worked as casual labourers and the sole woman worked as a washer. Cannery work often required individuals to remain in a small area for long periods and as a result they often bonded closely with the immediate people surrounding them. Ultimately, the cannery actively hiring families would help to provide a cohesive labour force and encourage a positive and familiar atmosphere by placing family members in similar roles.

Although being placed in similar jobs to other family members may have been a positive experience for workers, many First Nations employees were limited to specific jobs, especially women. First Nations women were rather unique in the fact that they represented such a large portion of a workforce that was largely dominated by men, however, women were also greatly limited in the jobs they were given and the majority of aboriginal women worked as washers. Other jobs most commonly given to aboriginal women included handfillers, net women, patchers and reform lineworkers. First Nations men were given more opportunities at the cannery and some of their roles included fishermen, ship captain, engineer, watchman and machine operator. Despite having more opportunity to pursue different jobs at the cannery, First Nations men were also very limited, and the vast majority worked as causal labourers. In comparison, the most common jobs held by white men in 1965 included engineer, bookkeeper and ship captain.

In summary, the records of employment for the North Pacific Cannery in 1965 revealed the unique position of First Nations workers. Many aboriginal employees were limited to working only July and August and yet this seemed to be mutually beneficial arrangement as the same individuals and families continued to return to the site every summer. The cannery was able to acquire a large workforce during its busiest months and the First Nations men and women were able to take advantage of good pay that didn’t interfere with subsistence living or other seasonal interests. Additionally, the cannery employed numerous First Nations families, which was much less common when examining the records of the other employed “ethnic” groups. Although the First Nations groups were employed on favorable terms and with larger family groups, they were also limited in their jobs. Most First Nations women were confined to a few specific roles and many of the men were limited to the lower paying jobs. Despite the reality of limited mobility, the North Pacific Cannery clearly provided an environment that First Nations workers agreed with, as the 1965 records show that families continued to return for work every summer.

Works Cited

Arnold, David F. The Fishermen’s Fronteir. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2011.

“Records of Employment, 1965.” In box M6 V.28, F1-7. North Pacific Cannery Archives, Port Edward, B.C.

[1] David F. Arnold, The Fishermen’s Fronteir (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2011), 73.